The politics of awarding Nobel prizes is sometimes as murky as war itself. This year, the Nobel Peace Prize Committee provided interim relief. It did not award Donald Trump the prize. Instead, it went to the Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado, a person whose slow politics has, in a way, helped birth an organic sense of peace for Venezuela.

The prize to Machado actually raises the question of the creativity of peace in India today. It’s in this context that one must raise the issue that discussions about peace and about Gandhian thought have been impoverished for the last three decades.

There have been two exceptions to this mode of thinking. The first has been the thinker Ela Bhatt.

Bhatt has often been seen as the founder of the Self Employed Women’s Association and nothing more. But in later years, she was in many senses deeply involved in peace and peacemaking with the likes of Jimmy Carter. She pointed out that peace cannot be worked out of a handbook. It is not a technology. Peace, she said, has to emerge as a metaphysic, out of the local languages, out of indigenous modes of thought. In this context, she emphasised that Gandhi gave currency to the words satyagraha, swadeshi and swaraj.

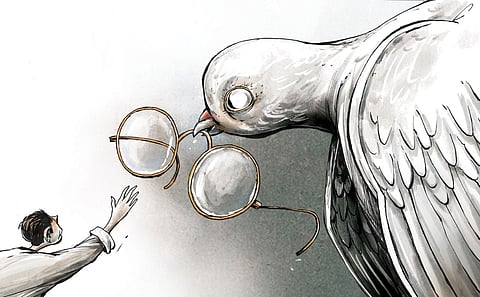

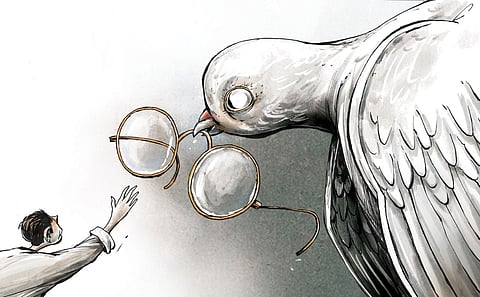

She also pointed out that peace has to be a form of storytelling. Without myths, stories, and inspiration of struggles, peace does not acquire the everyday clarity, resonance and poetics it desperately needs.

She said that one of the things to emphasise is the importance of the role of women in peace. She cited the examples of Manipur and Kashmir, where war was a known act, a ritual of waiting. She emphasised that when war becomes waiting, women seem to wait not only for peace, but for their husbands and children to come back every day. The final point that she emphasised—and I think it was very crucial—was that peace can’t be a contract. Peace, she said, in a deep and fundamental way, has to be part of a dialogue or conversation. It has to be built like a weave.

And in this sense, a sense of peace was very close to what C V Seshadri, the second intellectual thinker about Gandhism and peace, brought forth.

Seshadri was an extraordinary scientist, a chemist who built a laboratory in a slum that became one of the most famous research institutes of the country.

Seshadri regarded Gandhi as another scientist. Gandhi, in fact, was a senior ‘scientist’ whose innovative work he felt needed to be emulated. Gandhian innovation was a crucial part of scientific innovation. Seshadri emphasised that in a deep and fundamental way, Gandhian thought in peace required as much innovation as science. In fact, peace operated with less certainty than science.

He also emphasised two other things. Peace is not impersonal. It becomes autobiographical, and it’s the autobiography as experiments that often constitute the making of a movement, providing a deep sense of the values that go into the making of peace.

He differentiated between disciples and exemplars in any ethic. Disciples tend to follow the leader; disciples often mimic the leader. But an exemplar, in a deep and fundamental sense, is an innovator. S/he tends to go beyond the leader. In that sense, the exemplar is an original.

These thinkers pointed out that peace cannot emerge merely from instant contracts. Neither can it emerge from instant diktats of the kind Trump today provides. Peace is something that has to be worked and reworked on as a wheel. And the wheel is one of the most beautiful metaphors for peacemaking. One has to emphasise the importance of Seshadri and Bhatt today because there’s a paucity of thinking about war and peace.

Peace can never be just local. Peace, in a deep and fundamental sense, has to be both local and cosmopolitan, international. It’s in this sense that today if we think of peace, we think of the Gaza Strip.

Gandhi would have pointed out that there is a Gaza Strip in each mode of governance. One has to examine the Gaza Strip locally and internationally. In this context, we have to think simultaneously of what happened in Manipur and is happening in Kashmir.

Simultaneously, we have to provide a certain sense of peace, belonging, and kinship to what’s happening in the Gaza Strip, to Palestinians.

Both Seshadri and Bhatt differentiated between swadeshi and swaraj, explaining that these are not dualistic concepts. Rather, they merge into each other as part of a complex weave of microcosm and macrocosm. Swadeshi can never be purely local and swaraj cannot be merely holistic. Instead, swaraj must weave in the parts, because the parts make the whole.

The second point that Seshadri emphasised was the distinction between autobiography and choreography. He said that autobiography is the experiment of the self, and this self-experimentation is the beginning of peace. Choreography, then, is the collective attempt of the self to create holistic group peace, which demands a certain notion of memory.

Seshadri further emphasised that structures of violence are often more innovative than peace. Within this context, he pointed out that peace requires a richer, more fluid notion of goodness to capture the essence of what is happening today.

The final point he made was that peace is plural; it cannot be a monologue.

It must include several voices—the marginal, the migrant, and the normal. It cannot be achieved without incorporating a sense of marginality. We need to make a new connection between region, nation and the Anthropocene. We have to make sure that diversity, dialogue and plurality sustain both parts and the whole.

It is time we dream of the Anthropocene differently. We need to create a new sense of man with a new sense of nature more symbiotic than contractual. We need to create an ecology. This sense of ecology has to add to the new imagination of peace for the future to be a different kind of world.

Shiv Visvanathan | Social scientist associated with the Compost Heap, a group researching alternative imaginations

(Views are personal)

(svcsds@gmail.com)