Prime Minister Narendra Modi, during his short Manipur visit on September 13 that came after more than two-and-a-half years of confounding silence since a violent conflict had broken out between the Meiteis and Kuki-Zo group of tribes, announced nothing to appease either side in the conflict.

At the two public meetings he addressed—one at the Peace Ground in Churachandpur and the other at Kangla in Imphal—there were no hints that the demand of the Kuki-Zos for a separate administration of Union territory status would be considered, nor was there a mention of dismantling of the buffer zones created after the trouble broke out, or to ensure free movement for all along the highways, which the Meiteis want.

He did meet children from relief camps at both the venues. Although in his speech he made no mention of internally displaced persons (IDPs), Governor Ajay Kumar Bhalla, who accompanied him to both the places, did say in his address that a three-phase plan for having the IDPs return to their original homes is being worked out.

The expectations of the parties in conflict were dashed, but equally disappointed are the legions of commentators standing on presumed moral high grounds who have been pronouncing their verdicts on what is and what should be in all that has been happening in Manipur.

However, to be fair, what the PM ended up doing was somewhat inevitable. Unlike what many presume, this is not a bilateral matter between the warring groups. The Meiteis and the Kuki-Zos. Manipur is a multi-ethnic state, with 33 recognised Scheduled Tribes and several non-tribal communities that include the Meities, who form a thin majority.

Continual adjustments of the frictions and tensions among these communities have been the fabric of Manipur’s long history. Quite tragically, a sinew of sanity snapped in this process between Meiteis and Kuki-Zos on May 3, 2023, and a lot of the blame for this would have to go to populists who dangerously stoked and amplified the insecurities of either side.

If not for this catastrophic turn of events, all of the immediate causes of the nightmare the state is in could have been settled without resorting to violence. Eviction of encroachers from forest lands, the demand for Scheduled Tribe status among a section of the Meiteis, the fight against the spread of poppy plantations, illegal immigration from across the border—all of this could have been handled legally and consensually in ways where nobody ended up demonised or dehumanised.

Given this multiplicity of interests among Manipur’s many communities, even now, any plan for a lasting resolution to the present depressing crisis can only be after bringing all stakeholders on board, in particular the Nagas, who are the second largest ethnic group after the Meiteis.

This is especially so if the deemed settlement is territorial. Nagas and Kukis share virtually the same living space in the hills—with the Nagas claiming that most of the land Kukis are now settled on were and are theirs. Unless such matters are first put to rest, bigger trouble can be expected if nonconsensual settlements are pushed.

If the PM’s avoidance of matters directly related to the present conflict can be understood as inhibited by this constraint, what remains unforgivable is his two-and-a-half-year delay in coming here. Had it been otherwise, and had his government ensured the law remained strictly and solely in the hands of the administration, even if it meant dismissing the then BJP state government that was obviously not up to the challenge, the wounds suffered by so many ordinary people would not have been as deep, making reconciliation far easier. But better late than never.

One message was, however, clear from the proceedings. There will be no rewards for violence and all dispute settlements will have to be across the negotiating table. This is prudent, for once violence is allowed to become a bargaining chip, what British economist Paul Collier called a “conflict trap” can happen, and other players will begin using the same currency in the hope of similar rewards.

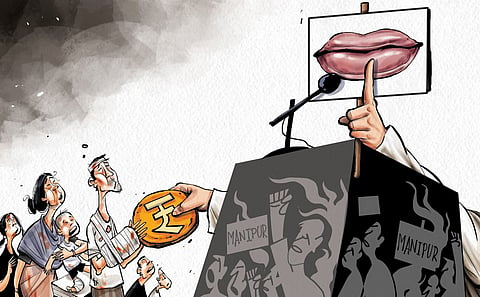

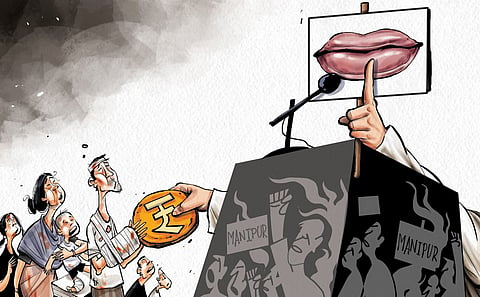

Other than these between-the-lines messages, it can be said the PM’s visit was no more ceremonial. Billboards and full front-page advertisements in all major local newspapers in Manipur on the morning of his arrival loudly spelled this out: he was coming to announce a total of ₹8,500 crore worth of projects for Manipur under the slogan ‘Viksit Bharat, Viksit Manipur’.

Of this amount, projects worth ₹1,200 crore were already completed and awaiting inauguration; these include two new Manipur Bhavans, one at Salt Lake in Kolkata and the other at Dwarka in New Delhi. The remaining ₹7,300 crore was marked for infrastructure projects to be launched across the state.

Hence, the mood in the state is a mix of relief and disappointment. Many are sore that nothing substantial was spelled out on strategies to resolve the current crisis. Kuki-Zos, in particular, were unhappy that their demand for bifurcation of Manipur to create a Union Territory for them was not taken cognisance of and one BJP MLA among them went public saying the PM’s visit was a waste of resources.

Many Meiteis, too, were sore that the PM was silent on their demands, such as their inclusion in the Scheduled Tribe list and highway protection. However, on their core concern of preservation of Manipur’s territorial integrity, they would be happy by what the PM indicated. He had generous praise for Manipur’s history, its contribution to the freedom struggle as a reward for which Andaman Nicobar’s Mt Harriet was renamed Mt Manipur in honour of the rebellious Manipur princes imprisoned there by the British. He also eulogised the contribution of the state’s athletes and artistes in bolstering India’s image.

In resolving Manipur’s problem, probably some kind of autonomy model will have to be thought of—either by strengthening the existing grassroots governance institutions, or by introducing new ones. But as the meaningful silences of the PM implied, this will have to be by consensus of all stakeholders, and not just of the two warring parties.

Pradip Phanjoubam | Editor, Imphal Review of Arts and Politics

(Views are personal)

(phanjoubam@gmail.com)