Once again, English finds itself at the heart of a national conversation. Several important questions are being raised. Some ask: Why shouldn’t India use English as a national link language? The counterview is: Why should English continue to dominate our lives in every sphere? Why do some people equate aspiration with English as a link language in a country so rich in its languages?

India’s civilisational history demonstrates our linguistic diversity never hindered cultural and social unity. In ancient times, languages used in different parts of our country flourished alongside pan-Indian languages like Sanskrit, Prakrit, and Pali. These languages enabled spreading of knowledge, spirituality and governance across the nation without displacing local languages. Trade routes, universities like Nalanda and Takshashila, and Bhakti and Jain movements thrived in a multilingual environment. India never needed a foreign language to stay intellectually or culturally united.

English became dominant in India, not by natural choice. It was imposed. The British deliberately positioned English as a marker of prestige and power. The arguments that English should be a link language remind us that we have yet to decolonise fully. Mahatma Gandhi’s opposition to English was grounded in linguistic self-respect, national unity, and decolonisation principles. He wrote in Young India in 1921: To give millions a knowledge of English is to enslave them… The foundation that Macaulay laid of education has enslaved us. There is no doubt that sole reliance on English as a national link language has the detrimental potential to reinforce social hierarchies and widen the divide between the privileged and the rest.”

The framers of the Constitution envisioned English as a transitional necessity—not a permanent feature. The Eighth Schedule recognises 22 Indian languages as vital to India’s identity and governance. The decision to uphold linguistic plurality was a defining feature of our constitutional settlement. The framers of our Constitution resisted the temptation to impose a singular language identity. To demand English as the central link is to dilute that foundational commitment to linguistic justice.

English serves as a tool of exclusion rather than integration, which was the original objective of the colonial ruler. It continues to be a linguistic filter determining access to quality education, jobs, and governance. Should we continue to perpetuate inequality and undermine the democratic ethos of equal opportunity by vehemently promoting English as a link language?

India’s intellectual and cultural legacy—from Ayurveda and mathematics to philosophy and literature—was built in Indian languages. Those who support English as a link language are directly or indirectly promoting the idea that Indian languages are inferior. When the vast majority of Indians believe English cannot be our national link language, they do not reject English. It is an assertion of India’s linguistic strength.

Many of the world’s most advanced nations do not rely on English as their national link language, even though they are multilingual. They have succeeded in science, technology, and governance while preserving linguistic sovereignty. These nations invest in their languages to sustain global engagement and cultural continuity. India, too, can be multilingual and modern without depending on English as a national crutch.

India is advancing in technologies like artificial intelligence, natural language processing, and speech-to-text tools to make Indian languages digitally capable. Platforms such as Bhashini and Anuvadini build robust multilingual tools that enable governance, education, and business in regional languages. Smartphones and platforms now offer interfaces that listen, respond, and serve in our languages. Knowing English is no longer essential.

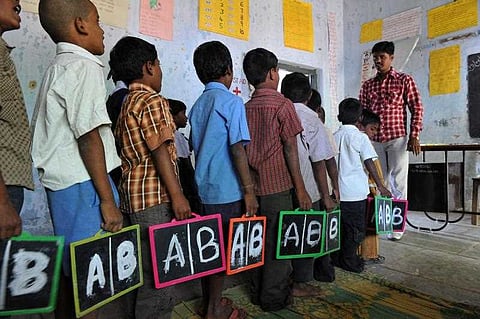

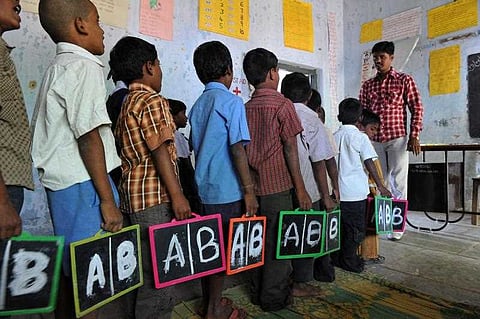

Democracy thrives when all citizens can participate fully. English as the national link language marginalises large sections of India—mainly rural and firstgeneration learners. According to the 2011 census, approximately 10.6 percent of the population reported the ability to speak English with varying levels of fluency. More up-to-date figures may become available once data from the forthcoming census is released. Courts, universities, and administrative systems operating primarily in English exclude those who think and speak Indian languages. Promoting Indian languages as functional languages of knowledge and governance is a democratic imperative.

As India looks ahead to its centenary of independence in 2047, we must redefine our linguistic priorities. All efforts must be made to create high-quality content, scientific research and technical education in Indian languages. AI tools should be developed to translate and generate knowledge across Indian linguistic systems. Governance should be accessible in the language of the people.

India’s strength lies in its diversity. English may have its place in the global sphere, but Indian languages must be given primacy in our national life. English can be taught as any other foreign language, but should not be promoted as a national link language. India can be both multilingual and globally connected without English as the link language. Should the India of 2047 still need English to dream big, build boldly, and lead globally—or will we have found the courage to do all that in the languages of our people? Let us focus on creating an ecosystem where India speaks in its languages—confident, creative and connected to its people. That is the true language of progress.

Mamidala Jagadesh Kumar | Former Chairman, UGC and O former Vice Chancellor, JNU

(Views are personal)