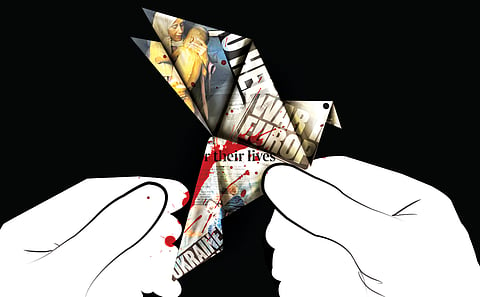

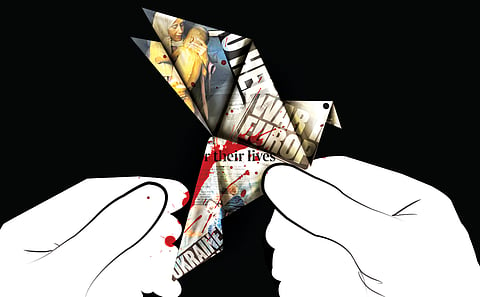

At a time when war seems to be a daily occurrence and an easy accompaniment to the nation state, thinking of peace is urgent.

One has to begin with a set of indirect observations. Literary critics have mentioned that poetry sometimes not only provides an aesthetics of insights, but can capture the truth of an event in a way social science is rarely able to. One wants to echo, in particular, the words of Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, who said, “Piecemeal peace is poor peace.”

One has to, first of all, begin by understanding that peace is not a question of fragmentary understandings. It’s in this context that one must begin by understanding what psychologist Ashis Nandy has repeatedly emphasised.

Nandy emphasised the impoverishment of international relations as a set of conceptual frameworks for capturing the idea of peace. He said international relations rely on fragmentary concepts like borders, securities, and contracts—none of which is able to create an organic sense of peace. It’s like expecting a cost-benefit analysis to create a commons.

It’s in this context that Ela Bhatt has argued that we have to go beyond dualism, particularly surrounding the idea of international relations. For this, we need to create a new kind of domesticity, one which encompasses international relations. She argued that being at home in domestic terms means being at home in the world—that the ideas of swadeshi and swaraj are both encompassed within the idea of peace. What is peaceful in the vernacular sense has also to be peaceful in the cosmopolitan sense.

This idea was taken up much earlier by Scottish biologist Patrick Geddes. He began by saying that the idea of peace requires not only a holistic worldview, but also a holistic knowledge system. Within this context, he pointed out that any idea of a knowledge system which is at peace with itself is both interdisciplinary, intercultural and international. His work ranged from contributions in urban planning to his work on Palestine and Ireland.

One has to emphasise the importance of memory. Here, Nandy becomes important again, who said memory sometimes haunts the hostilities of the world. He pointed out that many of the people who worked on partition as a subject had not experienced it. Theirs was a voyeuristic memory appropriated from their grandfathers and grandmothers. Many of the current communal forces, too, have voyeuristic memories of partition—there is little that is authentic about it.

Beyond memory and ethics, another issue of great importance is the role of the exemplar. Peace needs a new paradigm, but this paradigm can only be found embodied in the work of exemplars. For this, we have to go beyond Trumpian politics to an understanding of peace through figures like Mahatma Gandhi and Dag Hammarskjöld. These exemplars embody the idea of peace in an absolutely individualistic and unique fashion, and yet capture the spirit of universality that needs to inform every level of peace.

The second point one has to make is the importance of sacredness. Peace cannot be a secular contract. What one needs is a notion of the sacred, a notion of the holy, a notion which, to a certain extent, defines the possibility for peace in terms of what we can touch and touch gently. It’s in this context that Gandhi’s work on satyagraha has to be revived in a more international framework.

When Gandhi articulated his ideas, he did not encounter the idea of the concentration camp or certain kinds of violence. What we have to do today is to articulate how to stand up against violence, particularly the violence of terror. Satyagraha has to be reinvented, choreographed to create a new understanding of terror and how to blunt its threatening possibilities.

This has to be a question, not just of a new kind of theory but a new kind of practice that rewrites the ideas of the body, reworks the ideas of nature, and most of all, as philosopher Martin Buber pointed out, creates a new philosophy of the other. One has to transform the other from the warlike situation— from an ‘I-It’ approach, which views others as objects to be used or analysed, to an ‘I-Thou’ one, which is a direct encounter where individuals acknowledge each other’s wholeness and uniqueness.

Peace, in that sense, requires a theoretical, holistic, paradigmatic rethinking; but beyond rethinking, it demands that we relive our lives in terms of a new idea of life, livelihood and lifestyle. Consumption is as important as theory for eventually articulating the idea of peace. This needs a kind of rethinking which has to go far beyond the Trumpian contract, which is more like an ultimatum— at least it shows a series of violent threats, rather than any attempt to create a compassionate view of the world.

In contrasting Trump with the idea of the Dalai Lama, we get an understanding of what peace means in a holistic, paradigmatic sense today.

Two aspects of peace that we must emphasise. Firstly, peace has what might be called a performative aspect. This was brought out brilliantly in the processes of the Truth Commission, as they were held in South Africa and Rwanda. In Rwanda, professional theatre groups virtually activated the catharsis—the scripts, the plots required for a country to rework itself from genocide to peace.

Think of this possibility: what if the late Ratan Thiyam were to actually work in Manipur? He was someone who understood politics without being captive to politicians. He also had a deep understanding of the relation between Manipuri society and nature. What if Thiyam had activated a kind of truth commission based on the theatrical possibilities of Manipuri culture and dance?

Secondly, one has to emphasise that peace is pedagogy. Peace requires not just a constitution; it also requires a syllabus. It needs new categories and new ways of thinking.

In this context, one is reminded of the moral science books belonging to the Jesuits in the 1970s and 1980s. Here, moral science was not didactic. It was a discussion. It tended to work out ideas by providing exercises and working out small attempts at community.

Shiv Visvanathan | Social scientist associated with the Compost Heap, a group researching alternative imaginations

(Views are personal)

(svcsds@gmail.com)