The BJP has now firmly cemented its hold over the Hindi heartland with today’s sweeping mandate from Bihar, a verdict that marks the party’s first-ever emergence as the single largest force in the state assembly. For years, Bihar had remained the lone exception in the party’s otherwise uninterrupted arc of dominance stretching from Rajasthan in the west to Bihar in the east—covering Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and the Delhi NCR. That political map, almost entirely saffron, had one persistent gap. Bihar alone had resisted complete absorption. The BJP has ruled or is ruling every other state in this belt on its own; only Bihar kept it confined to the role of an indispensable, yet subordinate, partner.

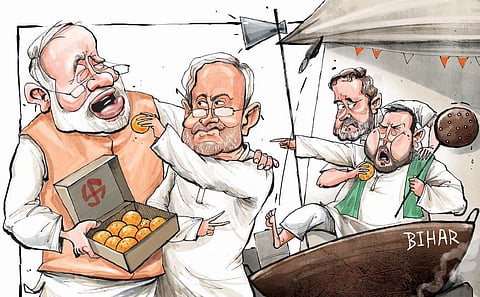

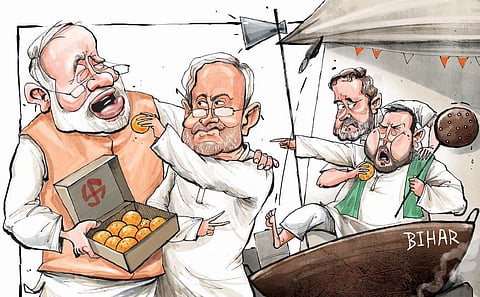

For decades, the BJP functioned as a junior ally to one socialist formation or another. First came the Samata Party (SAP), the force that George Fernandes and Nitish Kumar built as an alternative to Lalu Prasad’s dominance, which later transformed into the Janata Dal (United). Today’s verdict breaks that long and unusually consistent pattern. The NDA’s decisive win is not merely a tally but a structural shift: the BJP has overtaken the JD(U), seizing the pole position in a partnership that had historically tilted the other way. The margin—less than 10 seats—may look numerically modest, but politically, the symbolism dwarfs the mathematics.

The BJP’s strength has always been its instinct for alliance-making. Unlike the Congress, it is quick to identify potential partners, reach out across ideological lines, and stitch together functional coalitions. But its rise to power at the Centre changed the equilibrium. The party began to assume seniority in most alliances, subtly but firmly dictating terms. Nitish Kumar and the JD(U), fully aware of their irreplaceable relevance in Bihar’s political mosaic, declined to concede that upper hand. Their refusal shaped the state’s electoral chemistry for nearly two decades.

Nitish had considerable political capital. His reworking of Mandal politics—from a discourse centred purely on reservations to a broader promise of governance participation—earned steadfast caste loyalty. A series of targeted welfare programmes brought women voters to him in impressive numbers. The carefully cultivated image of ‘sushasan babu’ allowed him to maintain an aura of administrative credibility even while navigating coalitions with ideologically incompatible partners such as the BJP.

By contrast, the BJP entered Bihar with limited inherent advantages. It relied on its Jayaprakash Narayan lineage to open doors with socialist groups and prevent them from gravitating toward the Congress. It gathered the upper castes—long aligned with the Congress—under its banner, but that alone could not construct a winning majority in a state dominated by OBCs and Dalits. Bihar may have played a pivotal role in the Ram temple movement—after all, it was here that L K Advani was famously arrested by Lalu Prasad. Yet of the twin currents that defined the 1990s, Mandal decisively outweighed mandir. Hindutva remained a secondary force to the churn of backward caste and Dalit politics, even though the state witnessed occasional communal flashpoints such as Bhagalpur in 1989. Unlike Uttar Pradesh, however, Bihar did not experience repeated communal convulsions.

Although UP and Bihar are often clubbed as twin pillars of the Hindi heartland, the BJP has always treated them differently. Uttar Pradesh proved far more responsive to polarising politics, being the epicentre of the temple–mosque questions in Ayodhya, Varanasi and Mathura. Voting patterns echoed this receptivity: UP repeatedly swung towards the BJP, while Bihar required a broader BJP-plus formation. The RSS, too, had a far deeper organisational footprint in UP, with its extensive network of pracharaks and swayamsevaks enabling smoother cadre mobilisation. Moreover, UP offered the BJP a steady, recognisable leadership pipeline. Bihar, in contrast, still votes for Modi rather than any identifiable state-level leader. Crucially, UP’s Mandal moment was eventually subsumed into the BJP’s wider social engineering, enabling upper castes and significant backward caste blocs to cohabit within the political ‘parivar’. In Bihar, achieving such equilibrium proved possible only by leaning on socialist allies.

The BJP-SAP relationship flourished when George Fernandes was active. He brought ideological heft and offered the BJP a respectability it urgently needed after the Babri demolition pushed it to the margins in secular political circles. When Fernandes withdrew from active politics due to ill health, Nitish acquired the freedom to recalibrate his alliances repeatedly. He severed ties with the BJP more than once. While he fared well in state elections with the RJD and smaller parties, he suffered severe reverses in Lok Sabha contests. The 2014 elections—held after his acrimonious split with Narendra Modi, whom he had criticised for the 2002 Gujarat riots during the BJP’s 2009 National Executive in Patna—ended the BJP–JD(U) alliance despite the rescue efforts of L K Advani and Arun Jaitley. The Modi wave then swept Bihar.

The 2015 assembly elections, however, demonstrated that a JD(U) integrated into the Mahagathbandhan (MGB)—the grand coalition of socialists and the Congress—could effectively halt the BJP. Yet Nitish could not long manage the revived antagonism with Lalu Prasad. He returned to the BJP, and Modi, displaying unmistakable pragmatism, set aside the previous affront and reinstated him as chief minister. Bihar was far too critical to relinquish.

This election cycle, the BJP corrected its past errors. Amit Shah camped in Patna, entrusting micro-management to Dharmendra Pradhan and Vinod Tawde, both trusted organisational hands. Shah ensured the NDA functioned as a cohesive bloc, its constituents aligned rather than working at cross-purposes. Nitish, in turn, repaired his ties with Chirag Paswan of the Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas Paswan), enabling smoother vote transfers.

With the victory secured, the BJP’s real test begins: it must now evolve as a standalone force in Bihar and not merely as JD(U)’s companion. It must deepen its ideological footprint, build a durable social coalition, and craft a leadership bench that can one day command votes independent of Modi—all while maintaining the delicate balance that coalition politics in Bihar demands.

Radhika Ramaseshan | Columnist and political commentator

(Views are personal)