It is fashionable to say in India that we did long ago what the West is doing now—though not always with sufficient evidence. So what? Nationalistic licence can match poetic licence in stretching things.

Dictionary.com’s choice for word of the year 2025 has gone to a number—6-7, pronounced six-seven—which I understand is Gen Alpha slang for stuff that is run-of-the-mill or so-so. For the uninitiated, this is the generation born after 2010, as successors to Gen Z.

The wordly-wise website that conferred the dubious honour was candid in expressing its own confusion about the word, saying it is “meaningless, ubiquitous, and nonsensical”, with the hallmarks of ‘brainrot’—Oxford University Press’s word of 2024. It’s a long way from floccinaucinihilipilification, an old coinage meaning the act of estimating something as worthless.

Should we be at sixes and sevens over Gen Alpha exhuming an old English idiom that signifies a state of disarray or confusion? As a shudh-desi, I am a tad upset to hear 6-7 being described as new. In my not-so-humble patriotic opinion, its structure is a play on the old Hindi idiom, ‘Unees-bees ka farak hai’, meaning it doesn’t make a difference.

The venerable Cambridge Dictionary has come up with its own word of the year—parasocial—an intellectual-sounding word defined as a relationship felt by someone between themselves and a famous person they don’t know. It might break Gen Z hearts to learn that the word in question was, academically, first used circa 1956, when their grandparents were young. But then, today the celebrity afflicting the parasocial could even be an AI chatbot.

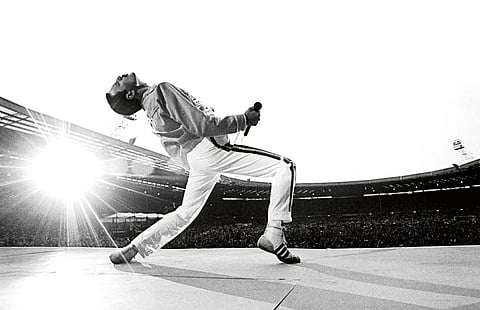

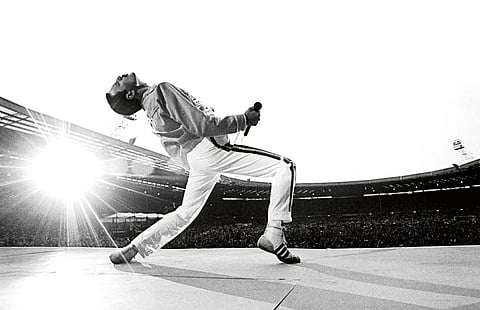

Six-thousand words have entered the Cambridge lexicon, including delulu, a derivation from delusional meaning believing things that are not real, often by choice. Now, I can argue with conviction that Freddie Mercury’s famous opening line from Bohemian Rhapsody—“Is this real life? Is this fantasy?”—was prescient about a delulu generation.

As a wordplay lover growing up at the intersection of many tongues, I think lingo-tracking can be a full-time job with a new generation emerging every 15 years or so. The young often invent new words to avoid adults, even while borrowing their ideas.

Words and expressions offer clues on how the world has changed, and with it, attitudes and perspectives. One of my favourite subjects is sociolinguistics, the study of language in relation to social factors such as gender, dialect, class, and region. We may add to that the increasingly important generation factor.

Take Tradwife, which was recently listed on both Dictionary.com and the Cambridge lexicon. It’s short for traditional wife—a woman who embraces traditional gender roles in marriage. What was common in the not-so-distant past, is still practised in most parts of the world, thanks to patriarchy. The word of choice used to be housewife. Sociolinguistically, that became a contested term as economies evolved: some would refer to a woman as ‘only a housewife’—as if she did nothing. For others, the term usually referred to an unpaid, homebound person who played many roles: cook, caregiver, relationship manager, psychotherapist, seamstress, and much else.

The journey from ‘housewife’ to ‘homemaker’ to ‘stay-at-home mom’ to the latest ‘tradwife’ reflects a social arc in which relationships are fluid and the family a fungible institution—a far cry from the patriarchal one-size-fits-all days. Tradwife also denotes a conscious choice of someone to be a homemaker, not one upon whom the status is thrust by social pressures.

Some words are pure-play generation separators, with not much change in the implied meaning. When I was a university student, the people later referred to as ‘cool’ were called ‘cats’, which was short for ‘hepcat’ to some, which meant a fashionable person in the jazz culture. ‘Hep’ and ‘hip’ have common origins in referring to those who follow the latest in style. Not to be undone by neo-colonial linguistic tyranny from America, a collegemate in Delhi once referred to a person as “Ati sheetal billi”, which was apparently the translation of an exalted student honour: “Total cool cat.” Macaulay may as well do a reverse swing in his grave.

Technology has thrown up words that are truly new, not just reverse-swingers as generation-separators. Words like selfie, trolling, and clickbait are difficult to imagine without a new tech-infused culture, unlike a hipster or hepcat. In my childhood, we used to mock the difficulties of translating post-industrial expressions into Hindi, with examples like ‘loh-path gamini’ (a vehicle that runs on iron tracks) to describe a train, which is now just rail-gaadi.

It is fascinating to separate the psychology behind words from the technology that thrusts new expressions upon on us. This exercise can be a pain for many because language-watching is not everyone’s ‘flex’—that word invented by Gen Z to describe the phenomenon of people boasting about something, especially on social media. Like many words, the context defines whether it is used in a positive or a negative way.

Take a deep breath. Soon, artificial intelligence will throw up new words, or new meanings of old ones. Or am I hallucinating?

Madhavan Narayanan | REVERSE SWING | Senior journalist

(Views are personal)

(On X @madversity)